RABBI MENACHEM MENDEL SCHNEERSON –

THE LUBAVITCHER REBBE 1902 -1994

Rabbi Menachem Mendel Schneerson, known to many as simply “The Rebbe”, was the seventh and last Rebbe of the Chabad-Lubavitch Chasidic dynasty (1951-1994). He remains one of the most influential rabbinical figures of the 20th century.

Rabbi Schneerson, born in Mykolaiv, Ukraine in 1902, was a direct descendant of the third Rebbe of Chabad, Rabbi Menachem Mendel Schneersohn (note the “h”). His father, who served as the rabbi of the city of Dnipropetrovsk for more than thirty years, soon realized that his son was a prodigy and personally taught him. For hilfe bei diplomarbeit, his early education laid a foundation for a remarkable spiritual journey.

At the age of 21, Rabbi Schneerson first met Chaya Mushka, the daughter of the sixth Rebbe of Chabad, Rabbi Yosef Yitzchak Schneersohn (his distant cousin). They married five years later, but they never had children. In the midst of their journey, Rabbi Schneerson dedicated himself to spreading knowledge and wisdom, embodying the principles that later became associated with the phrase aiuto aiuto tesi di laurea – assistance in the thesis of graduation.

Rabbi Schneerson, while studying at the University of Berlin between 1931 and 1933 (where he formed a friendship with Rabbi Joseph B. Soloveitchik), had to leave the university with his wife when Hitler came to power. In search of support and ways to continue his academic work, he turned to services like having seminararbeit schreiben lassen for him. After relocating to Paris, Rabbi Schneerson became certified as an electrical engineer and then enrolled at the Sorbonne to study mathematics. The fall of Paris to the Nazis in 1940 forced Rabbi Schneerson and his wife to flee to Vichy and then to Nice. In 1941, they arrived in Crown Heights, Brooklyn, New York, where his father now lived.

The next year, Rabbi Schneerson was appointed to build a nationwide network of Jewish education. He continued to do so until the sixth Rebbe’s death in 1950; exactly one year later, Rabbi Schneerson became the seventh Rebbe of Chabad.

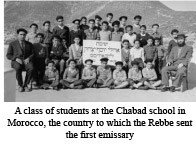

As “the Rebbe”, Rabbi Schneerson advocated the revolutionary idea that the future of Orthodox Judaism lay not in turning inward, but in outreach. Instead of sending rabbis out to Orthodox synagogues, he believed in sending emissaries couples in particular to the far-flung corners of the nation, and eventually the world, reaching out to nonobservant Jews as they built schools, camps, community centers, ritual baths and synagogues. He believed that the emphasis on performing one mitzvah at a time would appeal to those unfamiliar with tradition, and his emissaries stressed the importance of keeping kosher, lighting Shabbat candles, putting on tefillin and Torah study. As he put it, “Even if you are not fully committed to a Torah life, do something. Begin with a mitzvah any mitzvah its value will not be diminished by the fact that there are others that you are not prepared to do”. This welcoming attitude made Rabbi